What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it. (Simon 37)

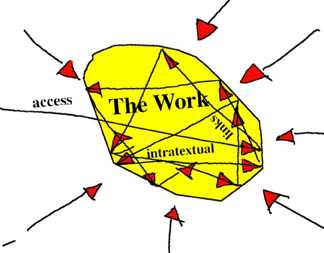

Figure 1.

The screen occupies a third position, between the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time. The screen and what it presents is a manifestation of the present, between past and future. Therefore the movement from space to time and the reduction from three dimensions to one, both halt at the position of the screen and its flatland of two dimensions. Obviously the design and composition of elements on the screen are of central importance to any critical study of hypermedia texts (Liestøl; 105).

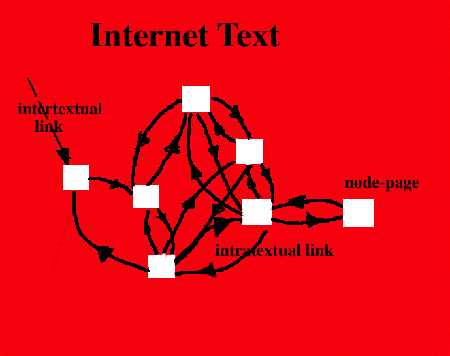

Figure 2.

Technologies and the Shaping of Narrative

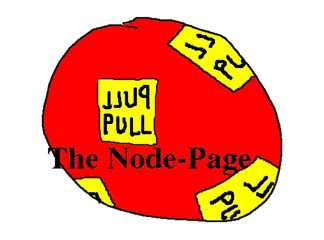

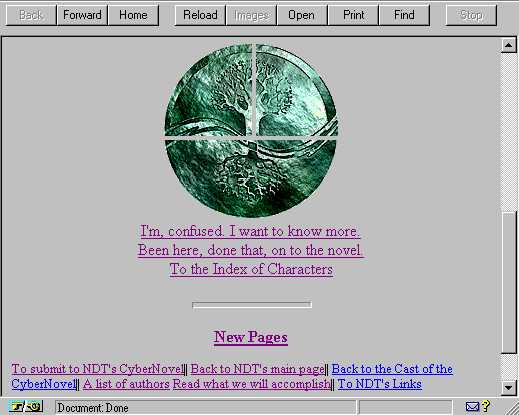

Figure 3.

Hypertext provides for multiple authorship, a blurring of the author and reader functions, multiple reading paths, and extended works with diffuse boundaries. With the inclusion of sound, graphics, video, and other media as nodes, hypertext expands the world available to the writer (Keep 1995b).

A Preliminary Discussion of Texts on the Internet

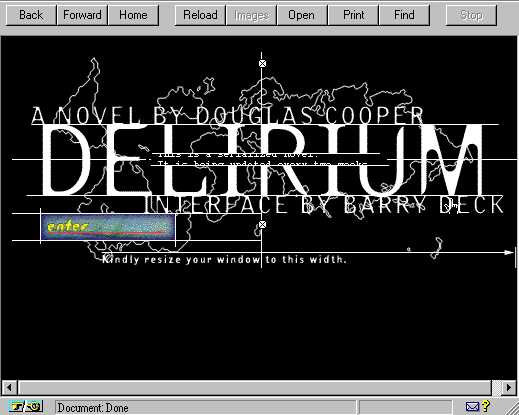

(cooper)

(Moulthrop)

(Joelle)

(Francis)

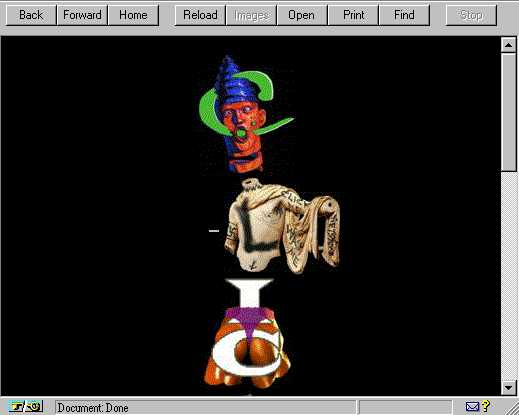

(Clarage)

C L I Cwe shall call these letter-image links. The "k" is a slightly distorted "boot" -- an image substitution for a letter -- which appears below c-l-i-c. And finally the word "me" appears. All letter-images are links to node-pages. Below the letter-image links (c-l-i-c), the image link (boot-k), and the word link (me) are the word- links "head," "heart," "glute," "boot," and "me" which directly correspond to and lead to the same path as the letter-image links. Their organization on the page emphasizes the paradigmatic organization potentiated by Internet textuality. Then below all this, there is a link to "My Graphic Interpretation of the Communications Decency Act of 1996." So in fact, the entrances are limited, but number seven. The following paragraphs describe some of the characteristics of the major node-pages. "Head." Through the link of letter-C-head image one enters a text which shows the head of a woman, reproduced many times, asking in a written text, "Why do you do/what you do/when you do/the net thing?" The words come up by progressive screen redrawing. This page of the text is entitled "dada Net Circus" and is linked to another page which alludes to information overload. On this page the woman now says: "mmm snorting information/we must visualize this." This image moves to a screen with a photograph in the center surrounded by yin/yang symbols interposed with binaries (1-0). The photo is of members of the Yanamamo tribe ingesting ebena. The combination of "the net thing," binaries, yin/yang, and ebena ingestion creates a metaphor for information as a drug. The linked sequence creates a visual pun: the computer, electronic information is the drug, the path, Tao. "Heart." The letter-L-torso link leads to the words "Cerebum Flatus" where automatic refreshing brings about an audio of Mozart's Faustus. This node-page is linked to Faustus 1, Faustus 2, Faustus 3, and Faustus 4. Faustus 2 displays a "typewritten" poem with a "hand written" image background. The hand-written image repeats the words "exhilarating moment." This too is accompanied with sound. Faustus 3 again repeats a word-image: "soul." This image too is accompanied by a poem and an audio. These images of writing replicate the probable origin of writing. Writing probably moved from image, cave painting, to abstraction, hieroglyph, character, or letter, to something immaterial, the beats on a computer keyboard (Bolter 1973). Faustus 3 takes the beats on a computer keyboard back to being an image, an image of writing. "Glute." Upon entrance to glute one sees nine image paths: one is an image of writing, and eight are anthropomorphic images of body fragments. One path makes use of fat-fitness humor. The only dead end path we found in the text happened to be here, in the glute. "Boot." In the image-letter boot-K a "Rock-o rides again" -- rock being a word image -- greets the viewer here. This image links to a tale in 23 chapters. Chapter 2 is entitled "In the back door of SinCity 24-hour rental joint" which is a satirically encoded tale. The verse/tale is an extended metaphor of intercourse as a 4-track tape insertion, and takes aim at censorship of the Internet. The link is to an electronic confession booth where there is an opportunity to interact through writing. "Me." Me contains "autobiographical" information. Of the texts we examined Click Me is by far the most experimental and exploratory with the new medium. It contains multiple references to the net-world, which is closed, sometimes solipsistic, often self-referential, and inherent in self-referentiality, ironic. Click Me is highly intratextual, extensively exploiting links. It is multimedia based, and contains various types of interactivity. The shortcoming is the lack of writing required by the reader, but there is some possibility for writing too. As the text defines itself in the "Me" section: "Netsam, flotsam, and jetsam" it contains odds and ends, vagrants and tramps, and the unreliable author/narrator indeed takes us for an ironic, irreverent ride.

(Blair)

Conclusion